Monkeypox Update: Cases Declining, But Disease Could Linger, CDC Report Says

Cryptopolytech Public Press Pass

News of the Day COVERAGE

200000048 – World Newser

•| #World |•| #Online |•| #Media |•| #Outlet |

View more Headlines & Breaking News here, as covered by cryptopolytech.com

Monkeypox Update: Cases Declining, But Disease Could Linger, CDC Report Says appeared on www.cnet.com by Jessica Rendall.

What’s happening

Monkeypox is still a threat in the US, but cases have been declining.

Why it matters

To stop monkeypox from becoming a disease that regularly circulates in the US, we need to slow the outbreak with tools like vaccines and testing.

What it means for you

Anyone can get monkeypox, but men who have sex with men are currently at higher risk. If you have an unexplained sore or think you may have been exposed, seek medical care and isolate if necessary.

Cases of monkeypox in the US are falling overall, compared with the peak of the outbreak in August, according to data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But to what extent monkeypox will keep circulating in the US — and the over 100 other countries experiencing the monkeypox outbreak — remains to be seen.

According to a CDC report released in late September, total elimination of monkeypox in the US is unlikely. The authors of the study note that “low-level transmission could continue indefinitely,” with most cases remaining concentrated among men who have sex with men.

While anyone can contract monkeypox through close contact, the majority of cases in the current, multi-country outbreak have been spreading between sexual partners who mostly identify as men. Temporary changes people who are at higher risk have reported making in their sexual habits, as well as the continued reach of the monkeypox vaccine, Jynneos, are some reasons cases have been declining in recent weeks.

At a Sept. 28 briefing, health officials shared promising new data on the effectiveness of the monkeypox vaccine: compared to people who did get vaccinated, people who were eligible but didn’t get the monkeypox shot were about 14 times more likely to be infected. Also in September, the CDC expanded the vaccine criteria slightly in order to include more people who might be at higher risk.

Here’s what to know about monkeypox.

Examples of monkeypox “pox” or rashes.

NHS England High Consequence Infectious Diseases Network

What is monkeypox?

Monkeypox is a disease caused by an orthopoxvirus that belongs to the same family as the viruses that cause smallpox and cowpox. It’s endemic in West and Central Africa, and reports of it in the US have been rare but not unheard of. (There were two reported cases in 2021 and 47 cases in 2003 during an outbreak linked to pet prairie dogs.) It’s a zoonotic disease, which means it’s transmitted from animals to humans.

However, this year monkeypox has rapidly shifted from a regional illness concentrated in African countries to a worldwide outbreak. Because of this, the World Health Organization announced in August that it’s changed the names of the two monkeypox variants or “clades.” The former Congo Basin/Central Africa clade is now known as Clade I, and the former West African clade is now called Clade II.

Clade II is the one currently circulating worldwide. It has two subvariants, and it’s typically less severe than Clade I. The (WHO)also has said that it’s working on finding a new name for monkeypox, which was named before current practices on messaging of viruses and diseases were in place. Those new practices include reducing stigma around a virus.

The current monkeypox outbreak might be linked to a case detected by a Nigerian infectious disease doctor in 2017, according to an NPR report. Dr. Dimie Ogoina identified a case with characteristics that more closely resemble monkeypox now, with cases spreading between men with a link to sexual contact. His and his teammates’ warnings to the broader medical community may have fallen on deaf ears as the outbreak spread beyond Nigeria, according to the report.

As of early August, monkeypox is a public health emergency in the US. The declaration was meant to open up more funding and resources needed to respond to the outbreak, including vaccines, testing and treatments. The Biden administration announced the formation of a White House monkeypox response team to advise the administration on how to stop the outbreak. The government’s response to the crisis was criticized earlier in the outbreak, in part over inadequate vaccine access and testing resources.

Is there a monkeypox test?

The test involves taking a swab from a lesion or sore to test for the virus that causes monkeypox. For people who first develop flu-like symptoms before lesions or sores appear, that may mean waiting for lesions or “pox” to appear. If you have symptoms, get tested and isolate at home.

If you were exposed to monkeypox but don’t have any symptoms, you don’t need to isolate, according to the CDC. But you should continue to monitor yourself for symptoms and take your temperature twice daily, if you can.

The CDC advises reminding your health care provider that monkeypox is circulating. If you think you have monkeypox but are turned down for a test, don’t be afraid to seek a second or third opinion to get the care you need. Testing availability is expanding as the outbreak progresses, but because symptoms can vary and monkeypox was previously rare in the US, health providers may initially mistake it for other illnesses.

The US Food and Drug Administration announced in early September that it’s now able to issue emergency use authorizations, aka EUAs, for monkeypox tests, which will allow more manufacturers to submit their devices to the FDA and hopefully increase access to tests in general.

What are the symptoms of monkeypox?

Symptoms of monkeypox in humans are similar to (but usually significantly milder than) those of smallpox, which the (WHO)declared eliminated in 1980.

A monkeypox infection can begin with flu-like symptoms — including fatigue, headache, fever and swollen lymph nodes — followed by a rash, but some people will only develop the rash, according to the CDC. The monkeypox rash or individual sores can look like pimples or blisters and can be found pretty much anywhere on the body, including the hands, genitals, face, chest and inside the mouth or anus. Lesions can be flat or raised, full of clear or yellowish fluid and will eventually dry up and fall off. For some people, they can be very painful.

You can spread monkeypox until the sores heal and a new layer of skin forms, according to the CDC. Illness typically lasts for two to four weeks. The incubation period ranges from five to 21 days, according to the CDC, which means people will most likely develop symptoms within three weeks of being exposed.

Though most people will recover at home, monkeypox can be life-threatening for some people, including young children, those who are pregnant and people with weakened immune systems. Out of more than 26,000 cases in the US, two deaths have been confirmed, with others being investigated.

Monkeypox doesn’t have the same ability to infect people that the virus that causes COVID-19 has, says Dr. Amesh Adalja, an infectious-disease expert and senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. Monkeypox is generally understood to not be contagious during the incubation period (the time between being exposed and symptoms appearing), so it “doesn’t have that ability to spread the way certain viruses like flu or SARS-CoV-2 can,” Adalja said, referring to the coronavirus.

Read more: Monkeypox Symptoms to Look Out For

How do you catch it?

Monkeypox mostly spreads between people through contact with infectious sores, scabs or bodily fluids, according to the CDC, but it can also spread through prolonged face-to-face contact via respiratory droplets, or by touching contaminated clothing or bedding. (Think the close contact you’d have with a sexual partner, the contact you have with strangers dancing at a club, or the contact you have with a household member whom you kiss, hug or share towels with.) Research is underway on whether (or how well) monkeypox can be spread through semen or vaginal fluid.

The “close” in close contact is a key element in the transmission of monkeypox. That, along with the fact that the virus that causes monkeypox appears to have a slower reproduction rate than the COVID-19 virus, sets it apart from the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Tom Inglesby, director of the Center for Health Security at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said in June at a media briefing.

The majority of the cases in the US have been in gay and bisexual men, with most of those cases linked to sexual contact. Gay and bisexual communities tend to have particularly “high awareness and rapid health-seeking behavior when it comes to their and their communities’ sexual health,” Dr. Hans Henri P. Kluge, the WHO’s regional director for Europe, said in a statement at the end of May, noting that people who sought health care early in the outbreak should be applauded.

At the press briefing on Sept. 7, Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, deputy coordinator of the White House National Monkeypox Response team, said that positive trends indicating the slowing spread of monkeypox “speak to the actions that individuals have taken across the country to protect themselves against the virus.”

“That includes changing their behaviors and seeking out testing and vaccines,” Daskalakis said.

Depending on where they live, people at higher risk of catching monkeypox, including men with multiple recent sexual partners, may be able to get a monkeypox vaccine. However, supply has been limited and some people have reported trouble securing an appointment.

Getty Images

How severe is monkeypox? Is there treatment?

There are two clades or types of monkeypox virus, according to the WHO: the recently renamed Clade I and Clade II. Clade II, which has been identified in the recent cases, has had a fatality rate of less than 1% in the past. Clade I has a higher mortality rate of up to 10%, according to the WHO.

Though the circulating strain of monkeypox is rarely fatal, according to the CDC, it can be very painful and may result in some scarring. Pregnant people, younger children, people with weakened immune systems and those with a history of eczema may be more likely to get seriously ill.

Antiviral medication like tecovirimat (TPOXX) can be used in people who are at risk of getting severely sick from monkeypox, according to the CDC. This treatment isn’t approved specifically for monkeypox (it’s meant for treating smallpox) and access to it has been restricted, with paperwork and strict ordering instructions. However, the CDC recently loosened restrictions around the drug. On Aug. 26, health officials said TPOXX should be even more available now and that there are “three times as many treatment courses as there are monkeypox cases.”

Monkeypox lesions progress through a series of stages before scabbing, according to the CDC. Though traditionally the rash starts on the face before becoming more widespread, monkeypox blemishes can be limited, resemble a pimple or other sore and aren’t always necessarily accompanied by flu-like symptoms.

Getty Images/Handout

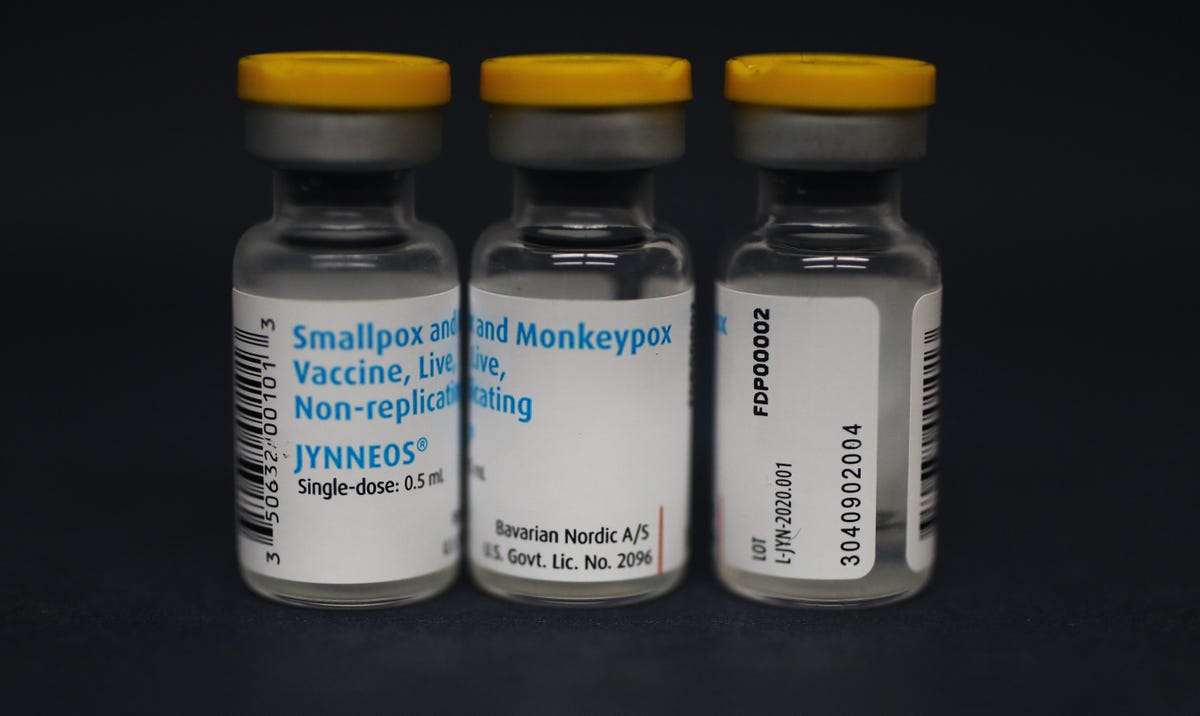

Is there a vaccine?

Yes. The US Food and Drug Administration has approved Jynneos to prevent smallpox and monkeypox. Because monkeypox is so closely related to smallpox, vaccines for smallpox are also effective against monkeypox. In addition to Jynneos, the US has another smallpox vaccine in its stockpile, called ACAM2000. Because ACAM2000 is an older generation of vaccine with harsher side effects, it’s not recommended for everyone, including people who are pregnant or immunocompromised.

Jynneos is the vaccine currently available to people who are at higher risk of getting monkeypox, or may have already been exposed to it. The FDA recently authorized a new way of giving people Jynneos that will stretch out the limited supply through intradermal vaccination, which requires a lower dose of vaccine compared to subcutaneous injection.

Recently, the CDC extended the criteria to include more people who are eligible for a monkeypox vaccine, though eligibility ultimately depends on where you live. Gay and bisexual men who’ve had more than one sexual partner in the past six months or a newly diagnosed sexually transmitted infection, people who’ve had sex at a public sex venue or public event, those who anticipate to participate in the above scenarios and the sexual partners of those folks should all be offered a monkeypox vaccine, per the CDC.

Vaccinating people who’ve been exposed to monkeypox is what Adalja calls “ring vaccination,” where health officials isolate the infected person and vaccinate their close contacts to stop the spread. But vaccinating people with a confirmed exposure, in addition to people at risk of being exposed in the near future, may be crucial to getting control of the outbreak, according to the White House’s chief medical adviser, Dr. Anthony Fauci.

Dr. Daniel Pastula, chief of neuroinfectious diseases and associate professor of neurology, medicine and epidemiology at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, said the vaccine is used in people who’ve been exposed but aren’t yet showing symptoms of monkeypox, because the incubation period for the disease is so long.

“Basically what you’re doing is stimulating the immune system with the vaccine, and getting the immune system to recognize the virus before the virus has a chance to ramp up,” Pastula said.

Though health care and lab professionals who work directly with monkeypox are recommended to receive smallpox vaccines (and even boosters), the original smallpox vaccines aren’t available to the general public and haven’t been widely administered in the US since the early 1970s. Because of this, any spillover or “cross-protective” immunity from smallpox vaccines would be limited to older people, the (WHO)said.

The information contained in this article is for educational and informational purposes only and is not intended as health or medical advice. Always consult a physician or other qualified health provider regarding any questions you may have about a medical condition or health objectives.

FEATURED ‘News of the Day’, as reported by public domain newswires.

View ALL Headlines & Breaking News here.

Source Information (if available)

This article originally appeared on www.cnet.com by Jessica Rendall – sharing via newswires in the public domain, repeatedly. News articles have become eerily similar to manufacturer descriptions.

We will happily entertain any content removal requests, simply reach out to us. In the interim, please perform due diligence and place any content you deem “privileged” behind a subscription and/or paywall.

First to share? If share image does not populate, please close the share box & re-open or reload page to load the image, Thanks!