The history of extreme right-wing politics in France

After incumbent Emmanuel Macron defeated far-right candidate Marine Le Pen in Sunday’s French Presidential election, European leaders were relieved that France would continue to uphold liberal norms for at least the next five years.

Macron beat Le Pen by 58.5 per cent of the vote, a margin that bellied how close the election actually was. Le Pen had been head-to-head with Macron leading up to Sunday and although the vast majority of polls predicted his victory, she was well within the margin of error. Moreover, with abstentions estimated at 28 per cent, the highest for a presidential election in 50 years, analysts say that the French electorate remains disillusioned with politics and distrustful of politicians.

Le Pen’s very position at the heart of this election signals worrying times ahead for moderates and minorities alike across France, experts say. With discourse and policy shifting towards the right, the political spectrum may already be fundamentally altered.

While the ideology followed by the far-right may seem novel, it traces its roots to two fundamental traditions of the French Republic, namely nationalism and secularism.

Nationalism

French nationalism began during the Age of Enlightenment but rose to the forefront after the Franco-Prussian war of 1870. Prior to the war, France could broadly be divided into two camps, one in favour of the republic and the other, against it. Those against the republic were defined by their desire to re-establish the French monarchy and were predominantly a fractured group with many competing interests. Resolutely defeated by the tactical genius of Otto von Bismarck, the war triggered a revolutionary uprising that further polarised the two camps.

A painting titled ‘the degradation of Alfred Dreyfus’ (Wikimedia Commons)

Then, with the trial of Jewish general Alfred Dreyfus in 1894, another intellectual movement emerged that upended the very notion of the nation and by extension, of nationalism. The Dreyfus affair, as it came to be known, evoked strong sentiments across France, with his supporters and allies equally impassioned by the strength of their convictions.

Dreyfus was eventually pardoned and later exonerated but his initial arrest sparked a debate over the definition of what it means to be French that carries on till today. The affair pitted Dreyfusards, who believed in his innocence, against the anti-Dreyfusards who considered him guilty.

Dreyfusards valued universalism and the rights of man, while the other group considered nationalism and traditionalism paramount. No one better represented this ideology than Charles Maurras, a popular monarchist writer who blamed Jews, Protestants, Freemasons, and immigrants for the French Revolution and considered them to be permanent threats to the nation.

The anti-Dreyfusards united the anti-republic French right, propelling the faction into dedicated ethno nationalists, anti-Semites and xenophobes. The group, aligned by the Dreyfus affair in their conviction to preserve the ethnic purity of France, banded together to form social clubs, newspapers, publishing houses and political parties.

Their efforts went on to influence many members of the Vichy government who theoretically represented the French state during the German occupation. While the Vichy ostensibly remained at war with Germany, history remembers them more accurately as Nazi collaborators.

Not only did the Vichy provide military assistance to the Nazis, but it also spearheaded the deportation of Jews from France. A study by author Simon Epstein proved a significant level of participation of the anti-Dreyfusards in the Vichy government, a natural if the more extreme successor to the anti-Semitic torchbearers from 1894.

The Dreyfus affair was also significant for its bearing on French secularism. The blatant bigotry it evoked, primarily from staunch Catholics, was one of the conduits for the famously French concept of separation of church and state. However, that secularism, known domestically as Laicite, originated in its early iterations nearly a century before Dreyfus was wrongfully arrested.

French secularism

The French Revolution of 1789 was as much a revolt against the Catholic church as it was against the monarchy. Many scholars argue that the primary cause of the revolution was rooted in public discontent over the massive amounts of money, power, and land held by the church in France. Between 1789 and 1801, the revolutionaries enacted a policy of dechristianisation which included seizing church property, exiling priests, and replacing Christianity with new forms of moral religion that drew on tenets of atheism.

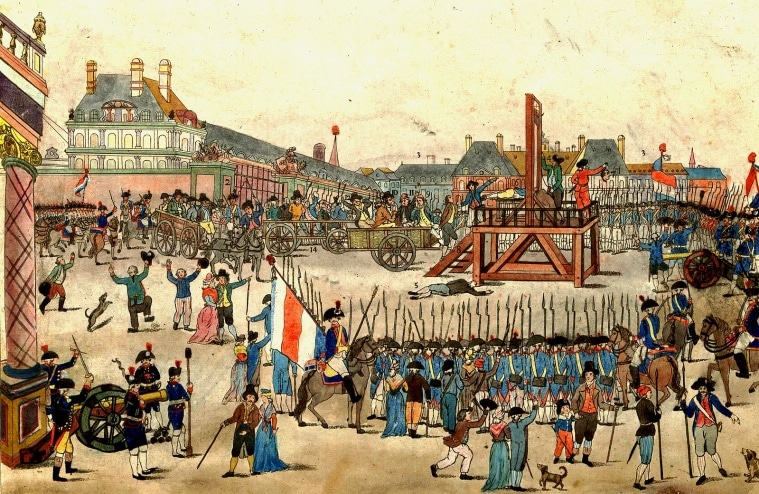

The execution of monarchists during the French Revolution (Wikimedia Commons)

The execution of monarchists during the French Revolution (Wikimedia Commons)

When Napoleon reinstated Christianity in 1801, he maintained many of the restrictions that the state had previously imposed. The church was to be subordinate to the state, the confiscated property was not to be returned, processions were restricted to a minimum and a few religious orders were permitted to exist. Importantly, Napoleon also decreed that other religions including Judaism were to have equal status with Catholicism.

In 1905, that policy was enacted into law which would entrench laicite or secularism across France, although it would only be known as such in 1958 when the term was enshrined into the French constitution. Laicite was meant to protect religious beliefs held by minorities but also to keep religion out of the public sector. That meant that no French state school could hold morning prayers, no President could be sworn in on the Bible, and no marriages would be legal if only conducted in a place of worship.

The policy was largely uncontested in the beginning and slowly faded into the background. However, all of that changed in the 1960s after the dissolution of the French colonial empire and the large-scale migration of former French subjects from North Africa which led to the emergence of a new generation of French-born Muslims.

Immigration and Islam reignited the old debate of what it means to be French and despite the unpopularity of the far-right after the Second World War, discontent nationalists once again found common ground with the ideas born from the Dreyfus affair.

The new French right

After the collapse of the far-right Vichy government, many were tempted to discredit the long-term appeal of extreme nationalism, tainted by the policies of Vichy and its association with the Holocaust, experts say.

However, the far-right continued to operate along the fringes, rising again to prominence with the creation of the Front Nationale (FN) in 1972. Founded by Le Pen’s father Jean-Marie Le Pen, by 1986 the party had secured an admirable 10 per cent of the vote in that year’s legislative elections. Le Pen has since made favourable comments towards the Vichy government and once dismissed the Holocaust as a minor “detail of history.”

After the 9/11 attacks, hyper-nationalism proved popular in France and in 2002, Jean-Marie made it to the second round of the French Presidential elections by campaigning on a platform drenched in anti-Semitism, xenophobia, and Islamophobia. After the initial shock of the attacks, and the wars that followed, Jean-Marie was once again relegated to the sidelines, criticised by the vast majority of French voters for his extreme views.

Marine Le Pen at an election rally (Reuters)

Marine Le Pen at an election rally (Reuters)

Since taking over FN leadership from Jean-Marie in 2011, Le Pen has worked to rebrand the party. She dismissed her father in 2015 and later renamed the party the National Rally. After losing to Macron in the 2016 elections, Le Pen doubled down on her efforts, convinced that the public’s tendency to automatically vote against the far right was the reason for her loss. However, despite this narrative switch, Le Pen remained fundamentally loyal to her father’s extreme policies toward immigrants and Muslims.

That in turn, remained tacitly popular amongst the French electorate. In a paper for Foreign Affairs magazine, a collection of authors state that “right-wing populists are much more willing to exploit cultural cleavages and blame economic problems on foreigners.” To Le Pen’s advantage then, France in the last decade has faced a host of economic problems and has profound cultural cleavages.

Le Pen capitalised on those divisions, stoking fears about the rising threat of Islamic terrorism and comparing Muslims praying on the streets to the Nazi occupation. Evidence of the pervasiveness of her message in theory and in practice can be found in numerous opinion polls. Discrimination against Muslims in France is prevalent across the country with a study by the French government finding that 42 per cent of Muslims and 60 per cent of women wearing a veil have experienced discrimination due to their religion. Polls also show that while 85 per cent of the public supported welcoming Ukrainian refugees, only 43 per cent wanted to welcome Syrians in 2015.

According to a report from the Berkley Center, “no other Western country goes so far in demonizing and criminalizing Muslim visibility in society through a disciplinary transformation of the principle of secularism.”

However, just as Le Pen’s popularity began to rise, a challenger emerged in the form of Eric Zemmour, a staunch ultraconservative who berated Le Pen for being too soft on immigration and the rise of Islam in France. Zemmour garnered support not only from Le Pen’s base but also from members of her family. While Le Pen had originally held the mantle of the far-right, Zemmour revealed that France was willing to go one step further. However, his extremism, while surprisingly popular, also helped paint Le Pan as a more moderate candidate, a feat that contributed to her electoral success this year.

Normalisation of the extreme right

When Macron won in 2016, he concentrated political power by straddling the centre. As a result, voters who did not support Macron were forced to align with the extremes, in this case, with Le Pen. By legitimising the far right, Le Pen and to a lesser extent, Zemmour, also normalised the weakening of liberal values.

A publication by Science Direct found that far-right parties in Europe embrace “exclusionist discourse” and another, from Freedom House, argues that they “threaten the fundamental human rights of members of minority groups, who increasingly face violence and intimidation at their hands.” Moreover, Justin Smith, a professor at the University of Paris, writes that far-right candidates regularly use misinformation to radicalise voters, a tactic that at first is targeted toward foreigners but later extends to all facets of society.

Alina Polyakova, a director at the Atlantic Council, further argues that not only has the right become electable, but its positions have also become more mainstream. Looking at European elections from 1990 to 2017, she found that when the line between the centre-right and far-right blurs, “the centrists inadvertently give more credence to ideas that were once considered too extreme.”

In 2003, at the height of Jean-Marie’s success, President Jacques Chirac, reacting to popular sentiment, appointed a 20-member commission to reconsider the requirements of laicite. Successive laws banned conspicuous religious symbols from state schools and public institutions, and later, full face-coverings from all public spaces.

After the murder of schoolteacher Samuel Paty by an Islamic militant in 2020, Macron, with Le Pen clipping at his heels, followed a similar adaptation strategy. Calling Islam “a religion that is in crisis all over the world today,” Macron introduced an anti-separatism bill that same year. The bill places strict control on religious associations, gives the state the right to shut down any place of worship, puts restrictions on asylum seekers, and bans residency permits for men who practise polygamy.

Macron’s Minister of the Interior, Gerald Darmanin, has attacked the sale of halal foods in grocery stores while his Minister of Education launched a campaign to combat “wokisme” fuelled by controversies around woke ideas like the use of nonbinary pronouns. Once the enemies of the far-right, secular leftist politicians have advocated for so-called Muslim bans, calling the headscarf incompatible with French values, and urging Muslims to be “discreet.”

During her concession speech on Sunday, Le Pen optimistically asserted that this campaign has been a “stunning victory” for her party. The fact that she has driven so many of her positions to the forefront of French political discourse may be evidence that she was right. Le Pen might have lost the Presidency, but her ideas, steeped in the history of the republic, are here to stay.